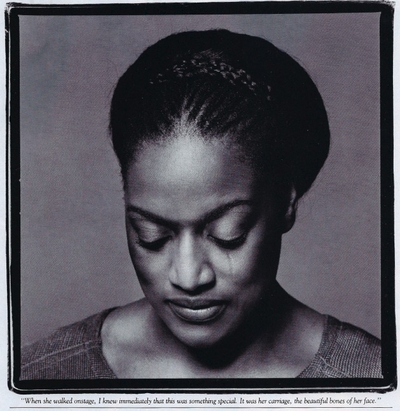

Jessye Norman, photographed for Connoisseur by Richard Corman.1986 |

"Man muss zuerst fragen!" she scolds, in ready German. "You have to ask first!" The fan murmurs an apology, mumbles for permission, gets a parting shot, and withdraws. The guards open the gates, and Norman's car rolls into the jammed labyrinth of Salzburg's narrow streets, her serene, uptilted profile framed in the window above the publicity portrait.

About her, there is the aura of a woman who knows where she comes from and where she is going. At forty, Jessye Norman has the musical world at her feet. She deserves her place at the top. Here is the assessment of Patrick J. Smith in the brand-new New Grove Dictionary of American Music: "Norman's commanding stature and stage presence have made her a major operatic personality, but her special distinction lies in her ability to project drama through her voice as well as histrionically .... Her opulent and dark-hued soprano is not always under perfect control, and at times sounds smaller than her frame would attest, but at its finest it reveals .uncommon refinement of nuance and dynamic variety." As her audiences know, the amazing thing is how frequently and reliably Norman is at her finest.

She has made some unlikely converts, among them Robert Wilson, the visionary theater artist who dreamed up Einstein on the Beach and other landmarks of the contemporary sensibility. He still recalls the first time he saw her, at a concert in Paris: "When she walked onstage, I knew immediately that this was something special. And I immediately thought I would like to work with her. It was her carriage, the beautifulbones of her face, the way she sat. First of all, the long, slow walk out onstage, and the way she sat and the way she stood."

This sketch and those that follow illustrate tableaux from Great Day In the Morning, a staged concert of Negro spirituals designed for Jessye Norman by Robert Wilson: "I always made her very small." |

"I really don't know about opera," Wilson confesses. "I've always hated opera. It isn't easy with Jessye either. I mean, it's easier. The thing about working with her is that she knows what she wants. She has natural instincts, but they're correct and right. I've seen her in shows by other directors, and she can be pushed in the wrong direction. But she knows what's right.

"In Noh theater, they believe the gods are under the floor. The contact with the floor is essential. With Jessye, the feet are firmly planted. And firmly rooted. The sound a singer makes isn't in the throat or whatever. the whole body makes the sound. With Jessye, it's from the toes to the tips of her hair. It's her ears, her elbows. The sound comes from the feet up. Because the feet are on the floor."

If Wilson's words suggest a static, marmoreal stage presence, that would be only part of the truth. In a climactic scene like that of Dido's suicide in Hector Berlioz's Les Troyens, she can summon up the fury and elemental abandon of a Kabuki tiger.

Many people, even musicians, never know except by hearsay that music can strike to the core of one's being. Norman found that out almost as long ago as she can remember. She has never forgotten the first time she encountered, at age ten, the singing of Marian Anderson, on a 78 of the Alto Rhapsody, of Johannes Brahms. "I heard her voice and I listened, thinking, 'But this can't just be a voice! A voice doesn't sound this rich and beautiful.' It was quite q revelation. And I wept, not knowing anything about what it meant. I just thought, 'It must be terribly important, this music.' " With appalled fascination, Norman read the pioneering black contralto's autobiography. She read the dignified accounts of the indignities visited on a black artist in the segregated America of the thirties and forties. She demanded that her mother tell her whether such things could be true.

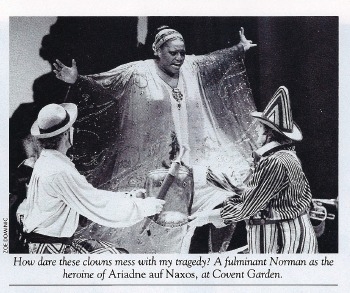

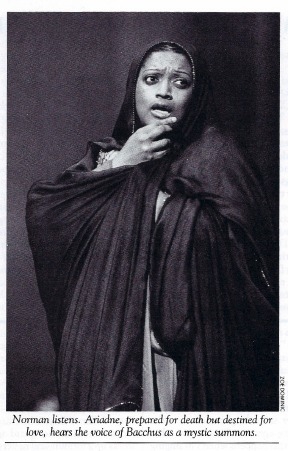

The answer must have taught her, earlier than most, to think hard about her own place on the world's great stage, and the habit has not left her. She does not read reviews and so did not hear until almost two years after the fact of the column by New York magazine's music critic, Peter G. Davis, in which he compared Norman's first Met appearance in Richard Strauss's Ariadne auf Naxos and Leontyne Price's farewell performance, as Aida, in the same house. Davis praised Norman's volatility and passion at the expense of Price, who, in Davis's view, had been inhibited and turned into a symbol by her status as the world's first black superstar in opera, and who artistic promise, he concluded, "was never fully realized."

The answer must have taught her, earlier than most, to think hard about her own place on the world's great stage, and the habit has not left her. She does not read reviews and so did not hear until almost two years after the fact of the column by New York magazine's music critic, Peter G. Davis, in which he compared Norman's first Met appearance in Richard Strauss's Ariadne auf Naxos and Leontyne Price's farewell performance, as Aida, in the same house. Davis praised Norman's volatility and passion at the expense of Price, who, in Davis's view, had been inhibited and turned into a symbol by her status as the world's first black superstar in opera, and who artistic promise, he concluded, "was never fully realized."

"What!" Norman demands. "What had he been waiting for? To open the new Met, as Price did, with new music no one has ever sung before! To sing Trovatore as no one has ever done before or will ever sing again! I just think people take incredible liberties saying what they think we ought and oughtn't to be doing.

"You see," she says, pressing on, "it would be completely impossible for me to have any kind of career if it hadn't been for people like Leontyne Price and Marian Anderson. Because, you see, of their strength of character." She recalls how the Daughters of the American Revolution barred Anderson from the capital's Constitution Hall. She recounts how a hotel refused to press Anderson's dress before a concert and permitted her to press it herself only if she went outside to do it in a dark alley. "I'm not sure I would have had the strength of character to go through with that. And to think of the poise, the beautiful singing she did in spite of it. So I can't sit still for people who would like to say that singers who have gone before those of us who are coming now, black American singers, have not expanded or whatever as they should have done. They've done more than anybody ever imagined. And those of us who have any sense are very grateful." She sits back, her features again composed in august serenity. "And very proud."

In 1961, at sixteen, Jessye Norman—a girl whose total musical experience up to that point had been singing at the dedication of every new recreation center, supermarket, and church annex in her native Augusta, Georgia—entered the Marian Anderson Music Scholarship Competition, in Philadelphia. "Miss Anderson's sister was running the competition at that time," Norman reports. "Miss Anderson herself was not there. Of course I didn't win a prize at all. I had no repertoire and had never studied singing, really. But they couldn't have been more encouraging, and told me to come back after I had studied. "

The judges at the competition were not the only ones to recognize Norman's untrained talent. On the way back home, the young singer and her chaperone stopped off to visit relatives in Washington, where Norman also sang an audition for Carolyn Grant, the head of the voice department of Howard University. She was promptly offered a full-tuition scholarship to come and study music—even though she was still too young to accept it. "There are tiny miracles that happen in life," Norman says with gratitude. (She has since endowed a scholarship at Howard in her teacher's name, though she prefers not to talk about that. It might sound like bragging.) "Singing isn't like playing the violin. We don't start having lessons at age three. The very best thing that could happen to a voice, if it shows any promise at all, is when it is very young to leave it alone, and to let it develop quite naturally, and to let the person go on for as long as possible with the sheer joy of singing—rather than being concerned with what comes later: the necessary concern over vocal technique. When I started voice lessons, I remember Miss Grant saying she hoped I would always enjoy the process as much as I already did, but that I would have the patience to learn exactly what makes singing possible, the purely physical aspect."

In four years at Howard, Norman learned her lessons well. After graduating, in 1967, she continued her studies first at Peabody Conservatory, in Baltimore, and then at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor. Under the terms of her fellowship, she also had to teach voice to students in other musical specialties. "I've always said that I don't think I ruined any world-class voices," she remarks cheerfully. Then, in 1968, the young singer took first prize in the female vocal division at the International Music Competition of the German Broadcasting Corporation, in Munich, and there was no more time to teach. Maestros like Colin Davis, Claudio Abbado, Riccardo Muti, and Rudolf Kempe were keeping her too busy.

In four years at Howard, Norman learned her lessons well. After graduating, in 1967, she continued her studies first at Peabody Conservatory, in Baltimore, and then at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor. Under the terms of her fellowship, she also had to teach voice to students in other musical specialties. "I've always said that I don't think I ruined any world-class voices," she remarks cheerfully. Then, in 1968, the young singer took first prize in the female vocal division at the International Music Competition of the German Broadcasting Corporation, in Munich, and there was no more time to teach. Maestros like Colin Davis, Claudio Abbado, Riccardo Muti, and Rudolf Kempe were keeping her too busy.

After a debut in 1969, Norman sang four seasons with the Deutsche Oper, in Berlin. "It's like walking through a mine field when you're a very young singer with an important contract at an important opera house in Europe," Norman observes. "They've got this whole long list of eighty operas, and you're meant to fill a need. There's no other reason for them to have you there. They haven't just taken you in out of the goodness of their hearts. You're there to work. And it's very difficult not simply to accept everything that's proposed to you, even the heavy dramatic roles in things like Parsifal or La Gioconda or any of the Leonoras—all of these things that were of course much needed.

"But I don't think the dramatic soprano voice is invented. I think it develops. I went to the opera all the time and heard so many different singers. And I started to notice things. There were so many singers who were not very old chronologically, but their voices didn't sound very young." Norman was not one to ignore such warnings. "I just decided," she continues, soon edging into a tense singsong that mimics her anxiety at the time, "not from anything except my own mind, 'I'm sure it must be exciting to sing Trovatore when you're twenty-five . . . but you probably oughtn't to do it.' "With an excellent new contract in hand but afraid of caving in to the pressures, she resigned. "People said, 'What courage.' It had nothing to do with courage. It had to do with survival."

Five years were to pass before Norman sang opera onstage again. In the meanwhile she spent time in Paris and then settled in London, where, perhaps quite unself-consciously, she picked up the classy Mayfair accent that still comes and goes. (She may say "straightaway" for "right away" and "mean" for "stingy," and call the famous concert series at the Royal Albert Hall "The Prumms," but she sounds not a whit less cultivated when she falls back into plain American.) Her career flourished in recording studios and concert halls, principally in Europe; and in due course she returned to staged opera. On September 26, 1983, the opening night of the company's centennial season, she made her debut with the Metropolitan Opera, as the prophetess Cassandra in Les Troyens. Her incandescent performance took America by storm—not altogether unexpectedly.

Moving into this phase of her career, she had retained Herbert H. Breslin, Inc., which masterminded (and still manages) the Pavarotti phenomenon, to handle her publicity. Even though the promoters got her on the "Today" show and into Life, which is the sort of thing they want most to do, Norman took stock and took charge. She broke with Breslin, explaining simply that being marketed "just doesn't suit me."

Moving into this phase of her career, she had retained Herbert H. Breslin, Inc., which masterminded (and still manages) the Pavarotti phenomenon, to handle her publicity. Even though the promoters got her on the "Today" show and into Life, which is the sort of thing they want most to do, Norman took stock and took charge. She broke with Breslin, explaining simply that being marketed "just doesn't suit me."

Without the winds of hype to fan the flames, Jessye Norman exerts—through talent, artistry, generosity, beauty, poise, and glamour—a power over audiences that is wondrous to witness, and nowhere more so than in Salzburg. From the moment she takes the stage, she simply basks in glory. She has her fans, of course, as what opera star has not?: the delivery boy for the Paris telegraph office whose adulation inspired the film Diva!; the electrician who drove from Cleveland in the dead of winter for her Ariadne auf Naxos at the Metropolitan Opera, waited at the stage door two hours after the final curtain to pay his respects, and .turned around and drove back to Cleveland; the choristers of the American Boy Choir, who last fall recorded with her an album of Christmas songs, due next December, and then lined up, all forty of them, to get her autograph. The Salzburg crowd, though, does not make a habit of getting carried away.

Drawn in the main from Germany's industrialist elite, these are people who come to Mozart's birthplace to take culture as at a spa they would take the waters. They dress up; they sit straight in their seats, don't cough, applaud when they are supposed to and not when they are not supposed to. At the end of a recital, they stay put for an encore, at most two, and then decamp en masse. But after Norman's all-Strauss program before a sellout audience in the festival's largest hall, they cheered for fifty-five minutes.

When a recital threatened to draw on longer than she wished, the great soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf used to beam a gracious smile and close the piano. Norman would not consider that an option. "You have to be able to pull off that sort of thing. I'm not sure that I'm quite ... We still had people, and we thought, We'll sing something, you know? I'll sing as long as I can stand." In Salzburg, she regaled her listeners with six encores.

When a recital threatened to draw on longer than she wished, the great soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf used to beam a gracious smile and close the piano. Norman would not consider that an option. "You have to be able to pull off that sort of thing. I'm not sure that I'm quite ... We still had people, and we thought, We'll sing something, you know? I'll sing as long as I can stand." In Salzburg, she regaled her listeners with six encores.

Underlying Norman's triumphs is an instrument unmatched in its combined sumptuousness, range, force, and expressivity. Although she usually bills herself as a soprano, her repertoire fans out equally over the soprano, mezzo soprano, and true contraltoliterature. Her working range runs from high C-sharp (silky or piercing, as the phrase requires) down through a voluptuous middle range to rich, resonant low A's and G's (one critic has called them "deep ruby-red"). As Death in Schubert's song "Der Tod und das Mädchen" (Death and the Maiden), she even delves to a low D that seems to enfold the maiden in dark, mystic consolation. In her voice, conductors hear many voices. In the last six months alone, she has sung the soprano part in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony for Sir Georg Solti (recorded by London Records) and Mahler orchestral songs in the central mezzo range with Claudio Abbado. Had a recording project of Leonard Bernstein's not fallen through, Norman would have sung for him the contralto part in Verdi's Requiem.

"I guess I place myself all over the place," she says with her melodious laugh. "And it doesn't worry me that some conductors with whom I've worked prefer to use me singing in the lower parts or the upper registers or whatever. It all depends, really, rather on what they have in their ownheads as a sound. For some conductors, the soprano is a very brilliant, bright-sounding voice, and if they hear a person who's singing B-flats and C's, but the voice is naturally a bit darker, they think of that voice as being a low voice, which is kind of their problem, really. But I don't allow myself to be cast in a particular repertoire—or only in a particular repertoire—because I like to sing what I'm able to sing. I like the voice to do what it can, rather than only what seems most comfortable. I don't pretend that I can sing everything because I can sing high notes and low notes."

"I guess I place myself all over the place," she says with her melodious laugh. "And it doesn't worry me that some conductors with whom I've worked prefer to use me singing in the lower parts or the upper registers or whatever. It all depends, really, rather on what they have in their ownheads as a sound. For some conductors, the soprano is a very brilliant, bright-sounding voice, and if they hear a person who's singing B-flats and C's, but the voice is naturally a bit darker, they think of that voice as being a low voice, which is kind of their problem, really. But I don't allow myself to be cast in a particular repertoire—or only in a particular repertoire—because I like to sing what I'm able to sing. I like the voice to do what it can, rather than only what seems most comfortable. I don't pretend that I can sing everything because I can sing high notes and low notes."

Nor are those notes, glorious as they are, an end in themselves. Norman has found from time to time that a well-vocalized early performance of a new piece, though not lacking "a certain credit," leaves her unsatisfied. She is not content, she says, "until the music becomes a part of me." For Mahler's oceanic song cycle Das Lied van der Erde, it took several years. Nevertheless, from the earliest entries in her long and distinguished discography (see box), she has consistently displayed an astonishing immediacy and interpretive finesse—qualities that have only deepened with time. As the Egyptian queen in the twenty-five-minute concert piece Cléopâtre, of Berlioz, she sustains a tragic grandeur through a jagged succession of episodes beginning in shame and rage, thence moving through lyric remembrance and doom-struck incantation to frenzied self-reproach and, after the snakebite, one dying flicker of renascent pride. The composer's fires set every facet of Norman's temperament flashin—all but her humor. Probably it is Jacques Offenbach who catches that one best. Asthe mythological heroine of his operetta La Belle Hélène, portrayed in the piece as a self-mocking flirt who can't help herself ("C'est la fatalité!")' Norman simply purrs with witty high spirits. Small wonder she causes a little war.

Whenever she sings, she knows what the words mean, every word. Apart from two short Ravel songs in Hebrew and some parts in Latin, Norman sings in English, German, French, and Italian, all languages she speaks. She is making a slow approach to Russian. "You see," she says, "I have a particular affliction. I am unable to say a word I can't spell. I can't just remember a sound. I can't learn a text pidgin fashion, because if I do, I can't ever vary the emphasis in any way, because I don't know where I am—where the verbs are, where the nouns are, and why the sentence sounds like this."

In preparing her material, Norman relies not only on words butalso on pictures. Ask her about Schubert's song "Der Zwerg" (The Dwarf), an enigmatic Gothic horror story in miniature, and she visualizes the scene on shipboard precisely. Mention Strauss's "Schlechtes Wetter" (Bad Weather), and Norman will describe the song's two characters, a mother and a daughter, down to the knot in a scarf. "I feel you have to see a picture. I'm not sure other singers work this way. I'm not sure this happens when I'm singing on the stage, but I need it as a reference in my own mind when I'm thinking about the song."

Jessye Norman, photographed for Connoisseur by Richard Corman, 1986 |

"But very often, I'm afraid that we go wrong. We don't plan enough, we don't have enough rehearsal time, and then opera can be less enjoyable. So rather than sing a lot of opera performances all over the place, I would prefer to do productions that have me in mind and that would suit me, and music that suits me. Because there are so many opera singers that it's crazy to sing everything that's offered. One should do things that suit."

By which she does not mean settling into a comfortable, predictable groove. Apart from her work with Wilson, there are such adventures in her future as a rendezvous—her first, its venue and vehicle as yet unannounced—with the anarchic young director Peter Sellars ("Boy, is he crazy or what!"). Though she names no names, she is on her guard against the sort of star director who works up a formula and never goes beyond it. They may captivate you once, Norman concedes, but not a second time.

"Because you know the tricks. A director has to have more than a bag of tricks. He has to do more than have columns and lots of fabric on the stage and a shiny floor. He has to do more than just be clever about how to move crowds around. And he has to allow—to have the faith in the intelligence of the people who have been hired to sing the roles—that they might have one or two ideas of their own that might work. Who knows?" Again, that Olympian laugh. "It might be found that what we do quite naturally is more suitable—for us—than what someone else might want to suggest that we should do. Of course, it can be that the ideas you have for yourself are really quite ridiculous. But at the same time, I feel there are too many directors who want to use singers as puppets. And that just is not right.

"I'm very serious about studying and knowing about what it is I'm singing and the part I'm supposed to be doing. And I'm afraid I do have an awful lot to say. Whether it's of any interest or not, I've got it to say. It just comes out of me, just from preparing my work, you know? If I sing the part of Phèdre , I read Racine. It only makes sense to me. I don't arrive at rehearsal waiting to have the hand of the director, which is the direct hand of God, of course, to explain to me what it is I'm supposed to be doing."

Her self-assurance today and the sense of harmony that goes with it spring in part from happy memories. "My parents were happy to have us, happy to have us around, to support and encourage us," Norman replies, when asked what inspired her as a child, "and that's a great thing. I had a lot of inspiration when I was growing up. Inspiration came from Babe Ruth. I refused ever to learn the ground rules of baseball, but just the inspiration to get out and try it and do it and be good at it, you know?—whatever it is."

In her enthusiasms, Norman has a sort of mercurial poise that keeps shifting aspect, like the shards in a kaleidoscope. "I love clothes, I love silks," she sighs, aglow with pleasure. "I love real fabrics—cottons and linens and silks and things. I love beautiful things. I love beauty in anything. I love beauty in an athlete, or just getting up very early in the morning for rehearsals. I love things that look lovely, very nice. A feast for the eye. It makes you feel good inside. I love the rain. It doesn't disturb. I love"—she draws the word out in a swooning glissando—"looking at racehorses. I love to see the horse in action, you know? There's such beauty in a racehorse. It's quite a marvel."

In her enthusiasms, Norman has a sort of mercurial poise that keeps shifting aspect, like the shards in a kaleidoscope. "I love clothes, I love silks," she sighs, aglow with pleasure. "I love real fabrics—cottons and linens and silks and things. I love beautiful things. I love beauty in anything. I love beauty in an athlete, or just getting up very early in the morning for rehearsals. I love things that look lovely, very nice. A feast for the eye. It makes you feel good inside. I love the rain. It doesn't disturb. I love"—she draws the word out in a swooning glissando—"looking at racehorses. I love to see the horse in action, you know? There's such beauty in a racehorse. It's quite a marvel."

In making her own marvels, Jessye Norman goes about with clarity of purpose. "A lot of people need chaos," she muses when asked what conditions her art requires, "and somehow emerges this wonderful performance. I cannot do it. I need order, I need calm. I need peace and quiet. I need fun! I need discipline. I need flexibility. I need all these things." And these, to an extent, are within her control. But an element no less vital lies beyond what can be planned. Probably her deepest secret rests in that boundless receptivity of hers—that openness to experience in all itsmultiplicities. What she has seen, what she has heard, what she has felt and known transmutes to music. Through her song passes the shiver of the sublime.

*

JESSYE'S JEWELS: HER BEST RECORDINGS

Jessye Norman's discography runs to some five dozen titles. Here are some of the best.

Berlioz. No composer seems to call on more of Norman's

countless moods. Her Les Nuits d' Été, coupled with Ravel's Shéhérazade(Philips), is splendid. Her Cléopâtre(on Deutsche Grammophon), on an album with Kiri Te Kanawa's performance of Nuits d' Été, is a stunner, as is her Cassandra, which may be seen as well as heard in the complete videotape of the Met's production of Les Troyens (Paramount Home Video).

Mahler. Norman's affinity for the composer's ironies and ripe Romanticism makes her recordings of Des Knaben Wunderhorn and Das Lied von der Erde especially treasurable (both on Philips). With the Vienna Philharmonic, she brings the right eloquence to the brief but crucial alto solos of his Second and Third symphonies (the Second, under Lorin Maazel on CBS Masterworks; the Third, under Claudio Abbado on Deutsche Grammophon).

Songs. Norman's dedication to the form has resulted in splendid albums of Brahms (two discs on Deutsche Grammophon, one on Philips, all recommended) and, even more exciting, Schubert (Philips). Twice she has participated, gorgeously, as one soloist among several in recordings devoted to the songs of Ravel. On both,' she sings the tinglingly sensuous Chansons Madécasses. (One, a selection of five cycles, is on CBS Masterworks; the other, the complete Ravel songs, is on Angel-EMI.) Her album of spirituals (Philips) rings with a beautiful openness.

Songs with orchestra. Norman's voluptuous performances of Chausson material, including Poème de l'Amour et de la Mer (Erato), are worth seeking out. No less remarkable are her readings, all on Philips, of Strauss's autumnal Four Last Songs; Wagner's Wesendonck Songs and the "Liebestod" from Tristan und Isolde; and the part of Tove in Schoenberg's Gurrelieder.

Opera. Except for her excellent Countess in Mozart's Le Nozze di Figaro(her earliest major recording; Philips) and Sieglinde, in Die Walküre (Eurodisc), Norman's operatic recordings take her into out-of-the-way repertory. Her liveliness and commitment make each piece an adventure. Top of the line: Haydn's Armida (Philips), Gluck's Alceste (Orfeo), and Offenbach's La Belle Hélène (Angel-EMI), in each of which she sings the title role.