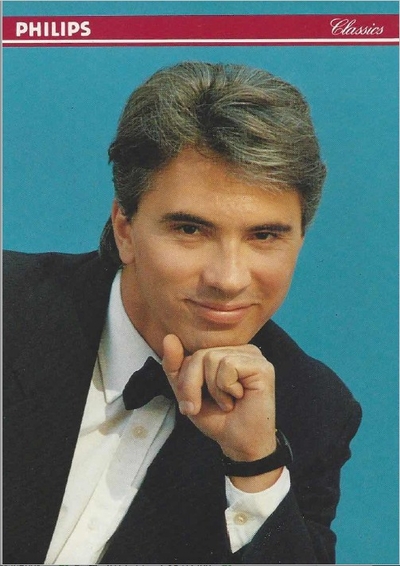

Maybe it would make a better story if I pretended I'd caught Dima before he ever set foot on American soil, but I'd be stretching the truth. Stealth appearances at lesser venues in Los Angeles and New York had not gone wholly unnoticed. Critics of renown (Martin Bernheimer on the West Coast, Will Crutchfield on the East) had praised him, if not quite to the skies. Back then, the New York Times was still insisting on transliterating the Cyrillic spelling of his name as Khvorostosky (as the copy desk stubbornly continued to do so even after the prestigious Philips label started releasing his first recordings as their exclusive artist, without the K). His signature silver mane had yet to turn, he was pencil thin, just starting to bulk up, and he wore black a lot, like an existentialist poète maudit haunting the Left Bank.

Maybe it would make a better story if I pretended I'd caught Dima before he ever set foot on American soil, but I'd be stretching the truth. Stealth appearances at lesser venues in Los Angeles and New York had not gone wholly unnoticed. Critics of renown (Martin Bernheimer on the West Coast, Will Crutchfield on the East) had praised him, if not quite to the skies. Back then, the New York Times was still insisting on transliterating the Cyrillic spelling of his name as Khvorostosky (as the copy desk stubbornly continued to do so even after the prestigious Philips label started releasing his first recordings as their exclusive artist, without the K). His signature silver mane had yet to turn, he was pencil thin, just starting to bulk up, and he wore black a lot, like an existentialist poète maudit haunting the Left Bank.

On a tip from an industry insider who plied me with pirate tapes, I flew to Dublin to profile Dima for Connoisseur magazine. This was in the late winter or early spring of 1990, by which time he had scooped up the grand prize as Cardiff Singer of the World, but social media had not yet been thought of, and wheels ground more slowly than they do now. The recital in Dublin was in a tiny private library pungent with the dust of moldering books, which was hard on Dima's larynx. His next engagement was a few days later at the far grander venue of Usher Hall in Edinburgh, across the North Channel and the width of Scotland. Before the flight over, Dima picked up a bottle of vodka at the duty-free, which he proceeded to knock back over the prohibition of the customs officials. Contrary to Connoisseur policy, I had booked first class, supposing Dima would be traveling that way. When the two of us checked in together, I quietly took a voluntary downgrade.

How we managed to communicate, I can no longer reconstruct. Dima's English was minimal, and all the Russian I had was da and nyet. Nevertheless, we managed to coordinate with a photographer dispatched, I believe, from London. Scouting locations, he had found a jetty projecting hundreds of feet into the Firth of Forth. On the boss's instructions, an assistant showed up with a bag of fish heads to attract seagulls. It was cold out there in the gusts and the spray, but the photographer kept urging Dima onward. When those fish heads started flying and the shutter started clicking, Dima put on the game face you see in the pictures, but having a concert to sing that evening, he was fuming. "If I am sick, you sing concert," he barked at me in the taxi back to the hotel, not being funny. When the car pulled up, he charged into the lobby and up the elevator without another word, vanishing from my life until his entrance onstage. Needless to say, he brought the house down. He bore no grudge.

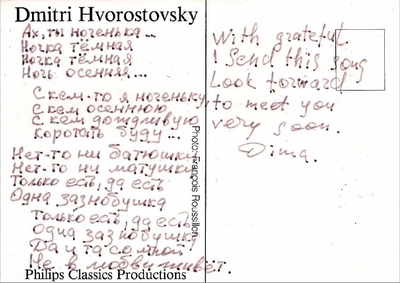

I had been especially curious about "Nochenka," a lament—a coachman's ballad, some called it—that Dima often sang unaccompanied as a final encore.

Getting him to translate the lyric for me had been a project. But after we had exchanged friendly goodbyes in Edinburgh, he wrote them down for me on a postcard that reached me as I was preparing my story. It has been on display in my office ever since. Here it is, reproduced for the first time.

Getting him to translate the lyric for me had been a project. But after we had exchanged friendly goodbyes in Edinburgh, he wrote them down for me on a postcard that reached me as I was preparing my story. It has been on display in my office ever since. Here it is, reproduced for the first time.

My story appeared in the June 1990 issue of Connoisseur under the title "Yesterday Siberia, Tomorrow the World," the text of which has long been available online, minus those spray-swept photographs (in which no seagulls appear), in a format that is far from reader-friendly. As a tribute to Dima, I've posted it here.

Maybe it's a little over the top? Henry "Dutch" Holland [sic], contributing editor to that late, lamented channel for New York dish and satire by the name of Spy, made great sport of it the following October, in his article "Signs of the Times," which was basically a takedown of what he called "extreme writing" in the paper of record and other print media. His barbs were wicked, but I'll say this for old Dutch: he quoted me verbatim, and he quoted me at length.

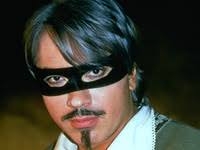

Invitation to an unmasking. Dima in Leporello's Revenge. |

A while after that jaunt north of the border, Dima and I got together for lunch at the Mayflower. The Mayflower... that white elephant at the southern end of Central Park West, shuttered in 2004 after a run of nearly 75 years. I can't be the only (ex-) New Yorker to feel nostalgic about the old pile. As long as I could remember, if you needed to track down operatic royalty passing through New York, your first call would be to the Mayflower switchboard. The Conservatory restaurant, off the lobby, functioned more or less as the Met's second, white-tablecloth canteen. Dima and I were meeting as friends there, free of ulterior agendas. After coffee, he asked me up to his suite to sit in on an interview with a top German magazine.

I demurred, but he insisted. "You know the answers to anything he will ask better than I do," he said with a grin.

For the first 20 minutes or so, all the reporter wanted to know was stuff covered in Dima's bio: where he was born, who his teachers were, what roles he had sung, what roles he would sing in the future, and so on. Then came the hardball, delivered in an accent worthy of Erich von Stroheim. "What do you think of contemporary German opera productions?" In other words, an open invitation to sound off on the boring hot-button topic of Regietheater, and the excesses of cutting-edge directors.

"You know," said Dima, "I've worked very little in Germany, and I really haven't seen many contemporary German productions."

"Yes," my colleague replied, but what do you think of contemporary German opera productions?"

I confess that when Von Stroheim decamped I rolled my eyes. In response, Dima raised his eyebrows. "They're not all like you," he said. I think I flashed on those flying fish heads.

Dima's appearances since the announcement of his brain tumor in June 2015, at the Metropolitan Opera and other international stages, were an inspiration. He carried himself not as a marked man but with composure, heart, and overflowing joy in the moment. At curtain calls, colleagues wept, and so did his fans, but they were smiling, too, and so was he.

Before I go, a few more words in that coachman's ballad. I had first heard "Nochenka" on one of my bootleg tapes. Right away, I dubbed a cassette for my father, who was born in pre-Revolutionary Russia and as a grown man would play his records of Russian songs on the phonograph, full volume, long, long past his children's bedtime. Not that my dad was thinking this way, but he and my mother were both nearing the end. Dima's singing, of "Nochenka" in particular, was the last great discovery of their lives. Though they never met Dima, they would send him their love, and he would send love back. At the memorial for my father, we played the cassette of "Nochenka," with Dima's knowledge and approval. Here's a link to a more recent performance.