Gottfried von Einem (1918-96) is a composer of whom we hear little these days. True, there's a (modest) bar and reception area at the Musikverein in Vienna that bears his name. And the centennial of his birth next year will not go unobserved: the Musikverein has announced a concert in his honor in January, with a revival of one of his operas at the fashionable Theater an der Wien to follow in March. But outside Einem's native Austria, who remembers?

Gottfried von Einem (1918-96) is a composer of whom we hear little these days. True, there's a (modest) bar and reception area at the Musikverein in Vienna that bears his name. And the centennial of his birth next year will not go unobserved: the Musikverein has announced a concert in his honor in January, with a revival of one of his operas at the fashionable Theater an der Wien to follow in March. But outside Einem's native Austria, who remembers?

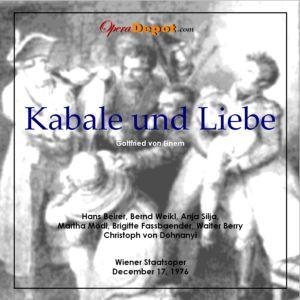

Growing up in Switzerland, I used to see his name now and then. In 1947, before my time, the Salzburg Festival unveiled Dantons Tod, after Georg Büchner, author of the dramatic fragment Alban Berg adapted as Wozzeck. In 1953, Einem got another shot in Salzburg with Der Prozess, from Kafka's novel. In 1971, the Vienna State Opera premiered Der Besuch der alten Dame, after Friedrich Dürrenmatt's international hit play, starring Christa Ludwig as the vengeful billionairess. Luminaries who followed her in the role include Astrid Varnay in Zurich, Kerstin Meyer in Glyndebourne, and Regina Resnik in San Francisco. In 1976, Vienna presented another Einem premiere: Kabale und Liebe, based on the same Friedrich Schiller play Verdi adapted more loosely and in Italian as Luisa Miller. (This list is not exhaustive.)

Decades ago, I saw Der Besuch der alten Dame in Zurich (Varnay was predictably tremendous), and made mental notes to investigate Dantons Tod and Der Prozess, should a convenient opportunity arise. So far, none has. But then, out of the blue, Kabale und Liebe turned up on my radar, live from the Vienna premiere, in the catalogue of OperaDepot.com.

Who in his right mind goes toe to toe with Verdi? Yet Kabale und Liebe is quite the discovery. Setting Schiller's German mostly if not entirely verbatim, Einem creates electric dialogue-in-music, supported by vigorous, atmospheric orchestral writing. The scenes--nine in all--are terse, with curtain lines that click like a lock. The murder-suicide, involving poisoned lemon squash and intimations of a dark, lonely road, has a tinta all its own. Scored with the utmost transparency, it flows slowly, fatefully, suspending time.

Under the baton of Christoph von Dohnányi, a multigenerational cast of all-stars delivers vivid character portraits. Not every voice is easy on the ear exactly, but this is hardly bel canto. As a strait-laced, class-conscious bourgeois mother, the legendary Marta Mödl wields her battle-scarred instrument for expressive advantage. An innocent ensnared by vicious manipulators, Luise finds an ideal interpreter in Anja Silja, who projects simplicity of heart, quiet despair, and ultimately an understated yet radiant clarity of purpose. Brigitte Fassbaender glitters in a more glamorous mode as her aristocratic rival. In the role of Ferdinand, whom both women love, the baritone Bernd Weikl bears an uncanny resemblance in timbre, attack, and accent to the young Jonas Kaufmann, difference in Fach be damned. The sound quality is high, with excellent balance between the stage and the pit—so much so that a listener conversant with German should be able follow the opera as easily as a radio play.

P.S. Among purveyors of live, archival operatic CDs and downloads, OperaDepot.com is far and away my personal favorite. Curiosities like this K&B are among the many reasons why.