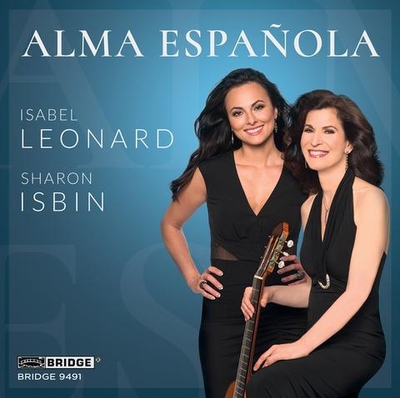

Folksong is a spring to which art song is forever returning. Federico García Lorca's Canciones españolas antiguas and Xavier Montsalvatge's Cinco canciones negras belong to a vast repertoire of homespun music of the people dressed up in its Sunday best for a "better" or at any rate choosier class of listener. Selections from both of these groups and others of like provenance feature on the new album Alma Española (Bridge 9491), a showcase for the bewitching talents Isabel Leonard, mezzo soprano, and Sharon Isbin, guitar. (Most of the arrangements are Isbin's own, substituting the real thing for an 88-key imitation.) We listened in on Lorca's epigrammatic and somewhat enigmatic "El café de Chinitas," "Las morillas de Jaén," and "Anda, jaleo,," with Montsalvatge's sensual lullaby "Canción de cuna para dormer a un negrito" and rambunctious "Canto negro" as encores. My studio partner Paul Janes-Brown found the performances lacking in "passion," by which he meant a gutsy, guttural gypsy edge. (I checked.) To me, that complaint is way off the mark. The point of such arrangements is never "authenticity." It's atmosphere. It's sophistication. Perfume. Who needs faux flamenco?

Folksong is a spring to which art song is forever returning. Federico García Lorca's Canciones españolas antiguas and Xavier Montsalvatge's Cinco canciones negras belong to a vast repertoire of homespun music of the people dressed up in its Sunday best for a "better" or at any rate choosier class of listener. Selections from both of these groups and others of like provenance feature on the new album Alma Española (Bridge 9491), a showcase for the bewitching talents Isabel Leonard, mezzo soprano, and Sharon Isbin, guitar. (Most of the arrangements are Isbin's own, substituting the real thing for an 88-key imitation.) We listened in on Lorca's epigrammatic and somewhat enigmatic "El café de Chinitas," "Las morillas de Jaén," and "Anda, jaleo,," with Montsalvatge's sensual lullaby "Canción de cuna para dormer a un negrito" and rambunctious "Canto negro" as encores. My studio partner Paul Janes-Brown found the performances lacking in "passion," by which he meant a gutsy, guttural gypsy edge. (I checked.) To me, that complaint is way off the mark. The point of such arrangements is never "authenticity." It's atmosphere. It's sophistication. Perfume. Who needs faux flamenco?

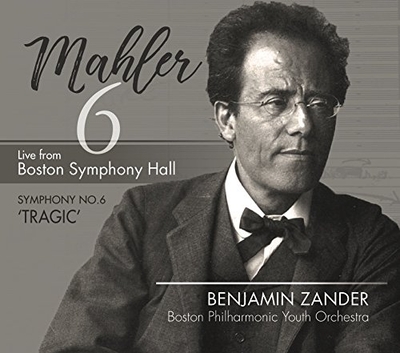

Next, we turned to Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 6 from Benjamin Zander and the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra (Brattle Media). A motivational guru much prized in corporate boardrooms, Zander is forever leading his recruits into deployments that test to the utmost the powers of expression as well as the technique of the most seasoned veterans. Within Mahler's Sixth, the transparency and calm of the Andante moderato movement pose what may be the greatest challenge for players with their whole lives before them. The temptation would be pour on the mock Weltschmerz, to playact sublimity distilled from experiences not yet within their grasp. There's none of that here. The music flows from hearts of innocence, as if for the first time. Hard to please as he can be, Paul opined that to him, "this wasn't Mahler," a critique apparently aimed as much against the music as the performance. Oh, really? "Mahler" straddles the extremes. Granted, there are movements of his symphonies that carry us to the very gates of Heaven and beyond or into the battleground of Armageddon. Yet the hush that precedes creation is likewise his domain, when all that is to be still hovers in suspense, barely known to itself, as here.

Next, we turned to Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 6 from Benjamin Zander and the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra (Brattle Media). A motivational guru much prized in corporate boardrooms, Zander is forever leading his recruits into deployments that test to the utmost the powers of expression as well as the technique of the most seasoned veterans. Within Mahler's Sixth, the transparency and calm of the Andante moderato movement pose what may be the greatest challenge for players with their whole lives before them. The temptation would be pour on the mock Weltschmerz, to playact sublimity distilled from experiences not yet within their grasp. There's none of that here. The music flows from hearts of innocence, as if for the first time. Hard to please as he can be, Paul opined that to him, "this wasn't Mahler," a critique apparently aimed as much against the music as the performance. Oh, really? "Mahler" straddles the extremes. Granted, there are movements of his symphonies that carry us to the very gates of Heaven and beyond or into the battleground of Armageddon. Yet the hush that precedes creation is likewise his domain, when all that is to be still hovers in suspense, barely known to itself, as here.

To close, we turned to Different Things, a recital disc from Marcin Markowicz, violin, and Grzegorz Skrobinski, piano (NFM 38). From an imaginative program also including unfamiliar works by Korngold, Schnittke, and Glass, we heard the Sonata in G major of Nino Rota. Movie lovers associate Rota's name with the soundtracks of Fellini, with the aching nostalgia of La Strada, say, or the carnival bustle of 8 ½. In a parallel career, Rota directed the conservatory in the southern Italian city of Bari for more than a quarter century (among his students: the young Riccardo Muti). In the sonata, I divine nothing of the academic. On a first hearing, what stands out is impeccable craftsmanship and an instinct for organic form, but most of all a gift for melody that cascades yet never rambles. The performance glows with purpose.

To close, we turned to Different Things, a recital disc from Marcin Markowicz, violin, and Grzegorz Skrobinski, piano (NFM 38). From an imaginative program also including unfamiliar works by Korngold, Schnittke, and Glass, we heard the Sonata in G major of Nino Rota. Movie lovers associate Rota's name with the soundtracks of Fellini, with the aching nostalgia of La Strada, say, or the carnival bustle of 8 ½. In a parallel career, Rota directed the conservatory in the southern Italian city of Bari for more than a quarter century (among his students: the young Riccardo Muti). In the sonata, I divine nothing of the academic. On a first hearing, what stands out is impeccable craftsmanship and an instinct for organic form, but most of all a gift for melody that cascades yet never rambles. The performance glows with purpose.