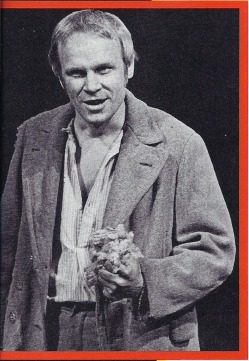

Jorma Hynninen as Topi in Aulis Sallinen's opera The Red Line. |

As the example of many American cultural centers from the sixties proves all too painfully, bringing the arts to life takes a lot besides bricks and mortar. The requirements for thriving opera are three: fine composers to write new pieces, fine performers to present them, and large, knowledgeable audiences eager to hear them. Only Finland has all three—and its resulting operatic renaissance is leaving the rest of the world way, way behind.

One man, more than any other, embodies the new spirit. The fact that he is the artistic director of Helsinki's Finnish National Opera is incidental. Much more important, he is a singer, a superb lyric baritone by the melodious name of Jorma Hynninen. (Pronounce the Finnish j like our y, and the Finnish y like the Frenchman's u in du. Stress each word on its first syllable; dwell on the double n: YOR-mah HUN-ni-nen.)

No singer has ever been endowed by nature with the full set of desirable attributes, but Hynninen comes closer than most. His strengths, to take quick stock, are a firm, handsome sound, evenly produced over its full, broad range and capable both of the grandest rhetoric and the subtlest shadings; deep musicality; a probing intelligence; dramatic flair; expressive features and a vivid presence; a fine ear for language. His limitations? At five foot ten, he could use an extra two or three inches. His other major failing is the flip side of his unswerving devotion to his material. It is disdain for self-promotion—almost a virtue. To Finland's leading composers, his artistry is proving irresistible, and they are centering their most important new stage works around him.

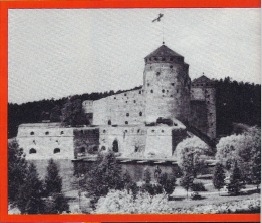

Olavinlinna, in eastern Finland, home to the outdoor Savonlinna Opera Festival. |

Outdoors, a treacherous stair descends to the courtyard. A white tarpaulin stretches from the ramparts down to the foot of a makeshift stage much wider from side to side than Cinerama. A short hour hence, with one stroke of their axes, to the roll of a drum and the clash and echoing shudder of cymbals, stagehands will cut the tarp's downstage moorings and it will rise, white and vast, on the barbaric pageantry of The King Goes Forth to France.

Aulis Sallinen, composer of The Red Line and The King Goes Forth to France. |

"It is very difficult, difficult also for us," Hynninen concedes. "Paavo Haavikko, who made the libretto, plays with words—very well he plays. We can always think, What is behind these sentences? And sometimes there is nothing behind. But the main line is clear." The British critic Rodney Milnes has aptly captured that main line. He regards The King as a "black Magic Flute, in that instead of tracing a journey from darkness to light, it treads a path from half light to pitch darkness."

High hopes have been riding on The King Goes Forth to France, the fifty-year-old composer's third opera, which came into being as a prestigious joint commission from the Savonlinna Opera Festival, London's Royal Opera at Covent Garden, and the British Broadcasting Corporation. Since the mid 1970s, when opera's Finnish renaissance began, Sallinen's work has come in for particular praise. The Red Line (1978), his second opera--in which Hynninen also had the starring part—has already left a deep impression (though not always the same one) in cities from Moscow to New York. A tale of hardship and political upheaval in rural Finland at the time of the Russian revolution, it did not please the Soviet critics, who condescended to it on ideological grounds, but in America its intense eloquence came through loud and clear. Donal Henahan, the chief music critic of the New York Times, greeted it as "the best new opera I have heard in many a year," comparing it to Alban Berg's Wozzeck and Leos Janacek's Jenufa, two of the handful of twentieth-century operas that promise to endure.

Contemporary opera, like the novel, is one of the embarrassments of late-twentieth-century civilization. The novel, for its part, is forever being pronounced dead. No one much bothers to say so, but except in Finland, contemporary opera, generally speaking, is dead. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when opera was the hopping, high-stakes mass medium that the movies are today, it fed on the raw energy of its own popularity, plunging straight into sex, romance, violence, power, revenge, money—all the juicy, messy things people really cared about and still do. These days, the appeal of new opera is cripplingly elitist. If a new piece gets a performance—a very big "if"—the best its creators can realistically hope for is some kind words from a sympathetic critic or two and short-lived enthusiasm from the first-night crowd. (Only time will tell whether Philip Glass's recent trance-to-music Akhnaten is the exception that proves the rule, or a nine-day wonder.)

In Finland, things are different. Last summer alone, 10,000 people saw The King Goes Forth to France, and many more were turned away. Like the other new Finnish works, this one may be serious, yet it is instantly accessible. As Okko Kamu, thirty-nine, the Helsinki Philharmonic's whiz of a music director, who conducted both The Red Line and The King Goes Forth to France, explains, "These operas speak to people because the material is close to their concerns. Difficult subjects and difficult music appeal to the Finns. They like to have a hard nut to crack." And as the tours have shown, the new repertory is as exportable as the equally serious and difficult Swedish films of Ingmar Bergman.

The non-Scandinavian world first took note of the blossoming of opera in Finland in 1975. The basso profundo Martti Talvela—internationally renowned as Sarastro, in Mozart's Magic Flute, King Marke, in Wagner's Tristan und Isolde, and especially in the title role of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov—introduced, at Savonlinna, Joonas Kokkonen's The Last Temptations, a somber but touching account of the last hours in the stormy life of a religious revivalist whose faith has given him no peace. The opera's success far transcended Talvela's personal triumph (in New York, it was performed impressively without him), and its repercussions have been tremendous. Since 1975, about twenty new Finnish operas have been brought to the stage, and they have been so good that when a Finnish premiere is announced these days, smart scouts take notice. Last year, Frank Dunlap, the director of the Edinburgh Festival, flew over to Helsinki in April for The Silk Drum, a Kabuki-inspired tale set to a jarringly modernist score by Paavo Heininen, and to Savonlinna in July for Sallinen's King. Now he is working on taking the Finns to Scotland. Meanwhile, John Crosby, the director of the Santa Fe Opera, has moved to acquire the rights to mount The King's English-language premiere, planned for the summer of 1986.

Hynninen's career has coincided exactly with his country's operatic new age, and it would be hard to overstate his importance in it. A farmer's son, he was twenty-one and in teachers college when a music instructor discovered that he had a good voice and packed him off to start studying singing "immediately." After finishing his training as a teacher, Hynninen worked at an elementary school ("like Martti Talvela, also") but also enrolled at Finland's preeminent music school, the Sibelius Academy, in Helsinki, for four years of further study. "I felt at the time that I must do all things very fast. There were quite a few young singers who had already made it to the top when I was just starting. But being older helped somehow. I had learned to work better. I always had to be practical. "

At twenty-eight, still technically a student, Hynninen took first prize in the national singing competition at Lappeenranta. In 1970, at age twenty-nine, he sang his first concert in Helsinki and joined the Finnish National Opera. After he had spent seven years mainly on home ground, impresarios all over Europe started issuing him fine invitations. He scored as Valentin, in Gounod's Faust; as Orff's Orpheus; as Silvio, in Pagliacci; and as Debussy's moody prince Pelléas. The 1977 season alone saw Hynninen's debuts at both La Scala, in Milan, and the Vienna State Opera, two of the top companies in the world.

Playing the circuit, however, was not for him. "Of course, an international career is good and very important. But an artist also needs a personal life. " His wife, Reetta, his son, Marco, twenty, and two daughters, Ursula, nineteen, and Laura, eight, come first. "If you really want to make a big and fast career, you must live in the international centers. I have traveled so much that I have seen what it is like in other parts of the world, and this is the thing that makes me want to keep some distance between my career and real life. I want to keep my own life, my own good things: a good family, a good homeland, where there is peace, a beautiful country, a pure land ... these things. And if it is possible, I would like to do only the most important things in my career. Naturally, it is difficult to have this kind of life and to become a bigger name. If the big career doesn't come, it doesn't matter."

The instant he won the prizes that performers live for, Hynninen turned his back on them with the resolve of a disillusioned courtier seeking out a desert cell. The decision cannot have been easy, but his timing was perfect. There was the right kind of work for him to do at home. His voice range was a lucky accident. So long as opera is predicated on romantic love, tenors take center stage. Love is not absent from the new Finnish operas, but they treat serious themes with grown-up sobriety. The lower voice of the baritone suggests a man of greater maturity, grappling with the adult world of individual and social responsibilities. Hynninen's temperament, too, was and is suited to such themes.

Sallinen is not the only composer for whom Hynninen has been the interpreter of choice. Another is Einojuhani Rautavaara, fifty-seven, whose writing is tinged with the sonorities of the Russian Orthodox Church. (He has the burning gaze of an icon.) Rautavaara appraises Hynninen in these terms: "His voice is beautiful and flexible, but real and strong. He is the most able singer we have had. Besides, his severity of character appeals to me. He's not a theater rat who will jump around and do anything. The new opera by my friend Aulis," he ventures, "is vocally made for him, but it doesn't suit him as drama. It does not express his personality." (A British critic surely judged right when he wrote, "To see that exceptional baryton noble Jorma Hynninen as the corrupted King [is] disturbing in precisely the way intended.")

Einojuhani Rautavaara, composer of Thomas, written for and dedicated to Hynninen. |

Hynninen's smile breaks slowly. His handshake feels binding, like a contract. He is a hard man to get to know. A hostess in the Washington diplomatic community recalls a formal dinner in his honor at which he spoke to no one all evening. At press conferences, he fades into the background—if he shows up at all. A critic overwhelmed by Hynninen's intensity during the Finnish National Opera's visit to New York asked to meet him and went away saddened to have found that Hynninen had no special wisdom to impart. Indeed, the two men could hardly keep a conversation going.

But onstage, Hynninen reveals himself totally; he holds back nothing. Performing new music has bred a fine self-reliance, a powerful indifference to received interpretations. Not one inflection of his singing is second-hand. Asked for influences, he names his teacher Luigi Ricci, in Rome, the inheritor of traditions going straight back to Puccini and even Verdi; and the Finnish pianist Ralf Gothóni, his steady accompanist for sixteen years. No singers? "Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau made lieder popular in the world today," Hynninen comments. "If we hadn't had Fischer-Dieskau, we would not have lieder today—I think so—so I admire him. He is the greatest lieder singer in the world nowadays. But somehow I'm also quite selfish and perhaps a little proud. I want to do everything the way I feel it myself." That, of course, has been the veteran Fischer-Dieskau's way, too, and many observers believe that—quite apart from his excellence in opera—Hynninen has inherited the intellectual German singer's title as the world's most spellbinding male recitalist.

He certainly has the range of responses to music. In Vienna, he is a Mozartean esteemed for his fine, aristocratic presence. In the brief but key parts of Christ in J. S. Bach's Easter oratorios, his plainspoken dignity conveys the stark, mystic radiance of the severe Lutheran God. He sings Verdi in broad, uncluttered phrases that soar with a romantic gallantry of spirit.

In all this music, his readings are, in a profound way, simple, controlled by a single, comprehensive view of the material. That same grasp of essences extends to writing that is far more volatile; it gives him variety. In the lieder of Schubert, Schumann, and his favorite, Hugo Wolf, Hynninen packs in interpretive details with such expressionistic fever—his voice thundering, then dropping to a hush, then mournfully caressing—that the intensity can become frightening. Some people can't stand it. Consider three top New York critics who reported on Hynninen's debut recital, at Carnegie Hall last September. After Will Crutchfield, of the New York Times, and Andrew Porter, of the New Yorker magazine, had taken strenuous exception to Hynninen's hair-raising reading of Schubert's song cycle Die Schöne Müllerin, Peter G. Davis, of New York magazine, rushed to the rescue, branding the singer's detractors "pedants" who had "completely miss[ed] the point of an extraordinary performance... Die Schöne Müllerin needs a good deal more than a beautiful voice, and Hynninen treated the cycle with an expressive warmth, concentrated intensity, and sense of cumulative drama that I have rarely, if ever, heard from a singer in this music." Hynninen's own assessment? "Gothóni and I agreed. It was the best Schöne Müllerin we have ever done. I am very sad if this kind of music making does not reach people in America. It is how we have to do it—absolutely."

The singer is one of the handful of performers one may be privileged to encounter in a lifetime who have held without compromise to their innermost convictions. He makes the classics sound immediate and the contemporary pieces sound classic. As a result, any engagement he chooses to accept becomes important by the fact of his having chosen it. And he is as busy as he wants to be. He records constantly—principally on Scandinavian labels not widely distributed beyond their regional market. His live engagements total about sixty evenings of opera and sixty concerts a year. (Plácido Domingo sings about seventy-five evenings; most stars log in about fifty.)

Whatever temptations come his way now, they have to fit into his timetable. His duties as artistic director of the Finnish National Opera keep him close to home, which is where his heart is. Besides, he says (surprisingly, given his datebook), "I want not to sing too much. Directing the opera will give me the opportunity to sing what I want, at home and also abroad." Concert engagements outside Finland are worked in as his schedule allows. (For his Carnegie Hall recital debut, which was on a Sunday afternoon, he flew in from Helsinki on the preceding Friday. Sunday evening, he flew back.) Since major operatic appearances on international stages demand extended time commitments, Hynninen is limiting himself to only two non-Finnish houses: the Vienna State Opera and New York's Metropolitan, where he has contracts through 1989, for the Count in Mozart's Marriage of Figaro (December 1985), Wolfram in Wagner's Tannhäuser, and the title role in Tchaikovsky's brilliant, melancholy Eugene Onegin. Still, he is flexible enough to bend his own rules. When the Bolshoi, in Moscow, invited him to play Onegin last fall, and to bring along the three other leads from the FNO's Tchaikovsky production, he sensibly did not decline.

Don Carlo in Savonlinna. Opera in Finland is by no means a strictly home-grown affair. |

Would he himself have been willing to cut back on his international activity if composers at home had not started writing for him? "That's really an important point. Nowadays it is possible for Finns to do something interesting and important in their own homeland. Ten or fifteen years ago our opera life was quite silent. Now we have many contemporary operas, and they have been quite good. You get something by being here, in this land: an interesting opera life, a living life." As opposed to a curatorial life caught up in the operas of the past? It feels almost impertinent posing the question to the man whose extraordinary voice and art have called forth so much of what is liveliest in music today.

The answer comes back in a fine Nordic understatement. "I have not thought it as you mean," Hynninen owns, "but somehow it may be so."