A surfeit of video: Krzysztof Warlikowski's "Don Carlos" at the Opéra de Paris. |

Paris

Hard fact is to drama as grit is to the pearl. Historians paint Don Carlos, the short-lived heir apparent to Philip II of Spain, as a twisted monster of depravity, a torturer of women and of animals and a dabbler in insurrection who died miserably in solitary confinement at age 23. More usefully for the purposes of romantic fictions, Carlos was briefly betrothed to Elisabeth de Valois, whom Philip, newly widowed, then took for himself instead.

Mind you, the junior royals, who had never met, were barely into their teens at the time. Yet in the Verdi masterpiece that bears his name, Carlos stalks the boards like a second Hamlet, an aggrieved crown prince who shakes the state to its very foundation. Suspicions of incest between him and the young queen are keeping the grizzled king awake at night. Orbiting the royal threesome are a pair of rival grandees with conflicting agendas: Princess Eboli, who (unlike her historical namesake) sleeps with the king but hankers for the prince; and the prince's imaginary soulmate Rodrigue, the Marquis of Posa, a champion of Flemish independence whom the king co-opts as his confidant.

The textual history of the operatic "Don Carlos" is messy in the extreme. There are two principal editions: the five-act original unveiled at the Opéra de Paris in 1867, and the swifter, significantly revised four-act adaptation prepared for the Teatro alla Scala, Milan, in 1884. In the first act of the Paris version, cut in Milan, Carlos visits France to appraise the total stranger he is meant to marry. The arc that remains takes place entirely in Spain, ending as it began, within the walls of a monastery. Thus, a narrative conceived as a suite of tableaux or Flemish tapestries acquires the claustrophobic symmetry of a mausoleum.

On Tuesday, Philippe Jordan, music director of the Opéra, and an all-star cast celebrated Verdi's 204th birthday with a reconstruction of "Don Carlos" as first delivered to the company in 1867. They even performed in the lean, elegant original French—a less self-explanatory choice than might be supposed. After all, one argument runs, Verdi's soul is Italian.

Naturally, the director pursued an independent agenda. In the words of the season announcement," Krzysztof Warlikowski strips down a tragedy haunted by ghosts, and places the intimate at the heart of an imaginary fresco truer than history itself."

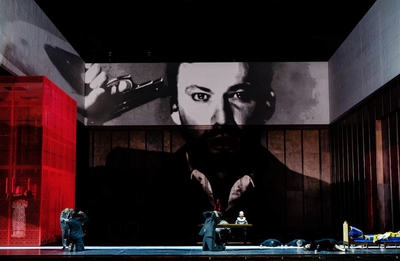

In concrete terms, this meant a high-tech yet largely featureless modern-dress production set mostly in a big wooden box. Pageantry was at a premium, even for the auto-da-fé, which involved a single heretic and no fire. In supercharged confrontations that cry out for the grand gesture, the players remained confined to their chairs. Wicked characters (and no others) smoked cigarettes. But Mr. Warlikowski placed his most distinctive accents with video projections. Giant black-and-white close-ups of the king, queen, and Carlos with a gun to his temple glaring into the camera landed with some force. Endless sequences of black and white spatter, like ancient film stock disintegrating as it unspools, induced twinges of migraine.

Mr. Warlikowski's contribution added up, in short, to a thoroughly routine instance of fashionable directorial practice, driven by arbitrary concepts, sparsely dotted with incidental epiphanies. Mr. Jordan's account of the score, on the other hand, flowed its tragic course like a mighty river, as if straight from the mind of the creator.

Unfurling the big picture, the orchestra painted the wintry forest, the monastery, the king's private chamber, and the prison in the darkling, gold-flecked palette of Rembrandt, while the sunshine and moonglow in the royal gardens (here a gymnasium and a vacant lobby, but never mind) glistened in the mind's eye like the brushwork of Velázquez. As Carlos, Jonas Kaufmann traced a fever chart from elation to spiritual exhaustion, seamlessly blending tenderness, tortured outcry, and ashen melancholy. The "holy torch of duty" that guides Elisabeth found its correlative in Sonya Yoncheva's blazing yet nuanced soprano, tireless over the course of a nearly five-hour evening. Ildar Abdrazakov's granitic, primal bass projected Philippe's terrifying façade without disguising the desolation within.

As Eboli must, the mezzo soprano Elīna Garanča—a glamour queen to set beside Nicole Kidman—cut the most scintillating figure in the carpet, inflecting her exotic musical arabesques with thrilling abandon. In a display of brute vocal force ill suited to his assignment, the baritone Ludovic Tézier roared through Posa's lofty oratory. The bass Dmitry Belosselskiy lent thunderous presence to the short but shattering role of the Grand Inquisitor, a diabolus ex machina poised to crush anyone in his way.

And how, ultimately, does the unreconstructed "Don Carlos" stack up against the revised "standard" version(s)? It answers some questions that few but pedants would think to ask (what is Eboli up to in the garden? what really goes down at the end?). The King and the Prince wallow at perhaps excessive length in competitive but melodious self-pity. Other changes are less conspicuous but vital to the pacing.

All in all, Verdi's second thoughts as a musical dramatist were seldom wrong. The final "Don Carlos" (preceded by the French act please) is the greater opera. But as this landmark revival proves, "Don Carlos" was a masterpiece to begin with.